Thomas Cole was the founder of what became known, posthumously, as the Hudson River School, the first American school of art. The School is known for its breathtaking landscapes. But The Course of Empire, which is by far Cole’s most famous work, rises above mere scenery. The series, which contains five paintings spanning the course of thousands of years, is one of the most potent works ever painted. One could argue that because landscape painting has the ability to play with the passage of time, it is able to communicate messages that transcend it. Cole’s The Course of Empire asks us to think beyond not only our own lifetimes, but across many generations extending both backwards and forwards through time, and as such was intended as a profound message to the American people if they are wise enough to grasp it.

At the present moment, we find ourselves in the middle image – Consummation. Many thousands of years have brought us to this ironic moment of both tremendous accomplishment and dangling over the precipice of self-induced annihilation.

The fourth image in the series, Destruction, is evoked by modern influencers and pundits in an attempt to lampoon our current situation, both in the West generally, but more specifically in the United States. Indeed, our nation is teetering, but the use of this image and the message that pundits try to convey with it always falls flat. Why is that? Because they simply have no idea what the series is about, its historical context, or philosophical outlook. This is due partly to ignorance, and partly to direct sabotage of America’s cultural heritage.

Thomas Cole’s work was not created merely for aesthetic pleasure, but rather, was an explicit effort to communicate philosophic ideas to his audience. In a letter to art critics in 1840 he wrote:

Many pictures have little merit beside that of gratifying the eye by mere dexterous imitation; but a good thought, a beautiful sentiment, even though feebly expressed, is of far more worth than the most skilful display of execution without meaning; and the works which possess the highest value, are those in which human genius manifests its greatest powers: those creations of master minds which, while they please by being true imitations of the beautiful of external nature, are the vehicles of noble sentiment, and poetical thought.

It would be impossible to understand Cole’s view of the purpose of art, let alone what he was illuminating in his art, if you were to view his work through the lens of modern art historians, pundits and pseudointellectuals from all sides of the Anglo-American “political spectrum.” Both conservatives and liberals shade their own twisted fantasies of death, destruction, decay and war onto Cole’s work, offering little-to-no outlet for Americans to take what was and still is a vital warning about the fate of our nation. Despite this, Cole’s warning still resonates almost 200 years since the artist passed in 1848 at the age of 47.

Even as a resident of the Hudson Valley, nestled between the Catskill Mountains and Hudson River — the very spot where Cole painted, lived and was inspired by magnificent natural beauty — I too fell prey to misinterpretations of his work. Initially I wrote him off as “a degrowther” simply because I hadn’t gotten to know him for myself. The keepers of Cole’s masterful artistic contribution have made an effort to control the context in which his work is viewed. It is hard to come by a description of Cole that doesn’t refer to him as a “proto-environmentalist,” or romantic conservative, worried about the rapid pace of industrialization in the New World. A 2018 write-up in The Magazine Antiques describes Cole as:

Horrified by the effects of industrialization on the landscape, Cole sent an impassioned visual warning to his fellow citizens about the harsh ecological cost of unchecked development of the land.

Betsy Jacks, the executive director of Cole’s estate, now a museum and dedicated historic site, says that he was “one of the first Americans to express environmentalist views at a time when people thought natural resources were endless. In his lectures and essays and with his paintings, he implored people to take better care of what we had, and to have more appreciation for it,” says Jacks.

But was Cole actually afraid of development and industry? Cole’s often-quoted and cherry-picked 1836 lecture Essay on American Scenery actually clarifies his position, stating the exact opposite as the designated authorities lead us to believe.

In what has been said, I have in general alluded to wild and uncultivated scenery; but the cultivated must not be forgotten, for it is still more important to man in his social capacity; it encompasses our homes, and though devoid of the stern sublimity of the wild, its quieter spirit steals tenderly into our bosoms, mingled with a thousand domestic affections and heart-touching associations human hands have wrought and human deeds hallowed all around. And it is here that taste, which is the perception of the beautiful and the knowledge of the principles on which nature works, can be applied and our dwelling places made fitting for refined and intellectual beings.

Cole did not want to eschew all development in favor of nature preservation. He was very much in favor of the cultivation of scenery done with taste and made fit for a population ever increasing in intelligence. He was not afraid of development and industry. He was afraid of development and industry done specifically without taste, or in a purely utilitarian fashion.

In his late 20’s, Cole traveled to Europe to study the great masters of art. He was both inspired by what he saw, but also saw room for improvement. Where Western society failed in Old World Europe, a New World opportunity presented itself in America. Though he was born in England, Cole was an American patriot through and through. In Cole’s time America was young and still making her way in the world. European society was (and still is in many ways) considered superior to American. Why did Cole valorize American scenery? Because he wanted the new nation to recognize the opportunity at hand.

There are those who through ignorance or prejudice strive to maintain that American scenery possesses little that is interesting or truly beautiful–that it is rude without picturesqueness, and monotonous without sublimity–that being destitute of those vestiges of antiquity, whose associations so strongly affect the mind, it may not be compared with European scenery… Let such persons shut themselves up in their narrow shell of prejudice. I hope they are few, and the community increasing in intelligence, will know better how to appreciate the treasures of their own country.

I am by no means desirous of lessening in your estimation the glorious scenes of the old world–that ground which has been the great theater of human events–those mountains, woods, and streams, made sacred in our minds by heroic deeds and immortal song–over which time and genius have suspended an imperishable halo. No! But I would have it remembered that nature has shed over this land beauty and magnificence, and although the character of its scenery may differ from the old world’s, yet inferiority must not therefore be inferred; for though American scenery is destitute of many of those circumstances that give value to the European, still it has features, and glorious ones, unknown to Europe.

It’s becoming clear by his own words that Cole did not want to prevent all development in favor of “preservation” of the Hudson River Valley. Historians rewrite Cole as conservative, and averse to change. On the contrary, Cole envisioned a beautifully cultivated Hudson River Valley.

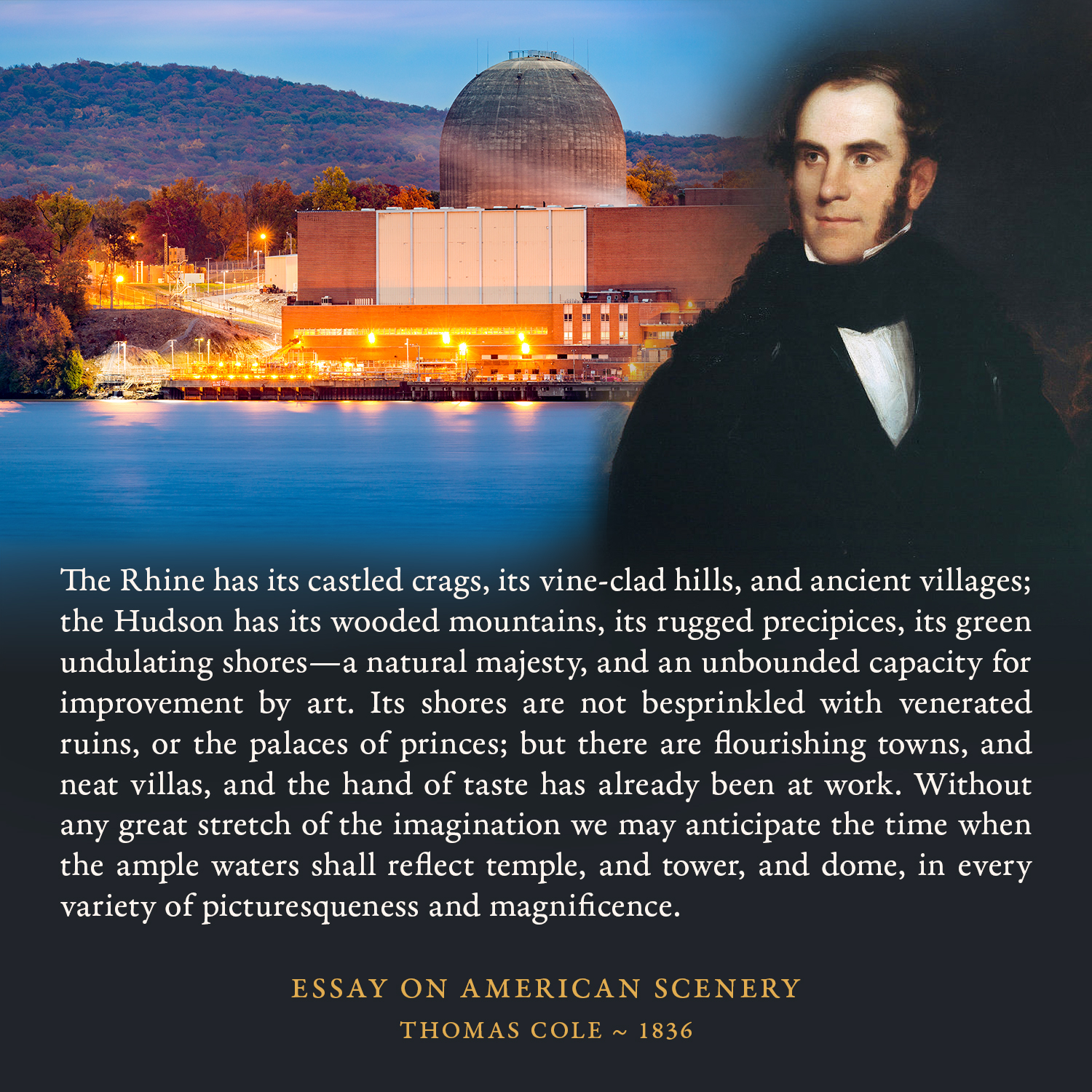

The Rhine has its castled crags, its vine-clad hills, and ancient villages; the Hudson has its wooded mountains, its rugged precipices, its green undulating shores-a natural majesty, and an unbounded capacity for improvement by art. Its shores are not besprinkled with venerated ruins, or the palaces of princes; but there are flourishing towns, and neat villas, and the hand of taste has already been at work. Without any great stretch of the imagination we may anticipate the time when the ample waters shall reflect temple, and tower, and dome, in every variety of picturesqueness and magnificence.

Perhaps he had a premonition of the Indian Point Power Plant as the dome reflected in the water.

Historians wrongfully categorize Cole as a conservative or romantic, but it is clear from his own words that the inverse was true. What historians categorize as fear of the future, was actually a deep concern for it. In his 1845 Lecture on Art, Cole explains that he wants to

“… lead to the consideration of American Art and to suggest what appears to be incumbent on us as a community if we desire to sow seed in the fields of the Beautiful which for ourselves and the coming generations shall grow and ripen into abundant harvests. Pregnant with life the air we breathe surrounds the natural world and softens into harmony its rugged forms. So Art—the Atmosphere which encircles the sphere of our humanity—kindles the dead soul and raises it above the dullness of mere animal existence to intellectual acquirement.”

Cole continues by quoting Schiller:

For through the morning-gate of beauty goes

Freidrich von Schiller, The Artists, 1789

The pathway to the land of knowledge!

The Course of Empire, as previously stated, is without a doubt Cole’s most potent work. It is hard to scroll through an internet political feed without seeing the images referenced. But whether it’s being leveraged by low-life social media clowns for racist demagoguery, or in the high halls of academia by Green Malthusian liberal professors, it’s always misinterpreted.

The third painting, Consummation is the crux of the work, and so holds the keys to understanding the meaning behind Cole’s allegorical opus. As Cole wrote for the description to Consummation:

The architecture, the ornamental embellishments, etc., show that wealth, power, knowledge, and taste have worked together, and accomplished the highest meed of human achievement and empire. As the triumphal fete would indicate, man has conquered man – nations have been subjugated.

America, a freshly minted nation in Cole’s time, was formed as a bulwark against the British Empire which was – with its East India Company – the preeminent embodiment of subjugation and a conqueror of mankind. He painted the series between 1833-1836, and we can read directly from his journal what genuine fears were fueling his work.

August 21 [1835]

I have of late felt a presentiment that the Institutions of the United States will ere long undergo a change, that there will be a separation of the States. Riot and public murder are common occurrences, every newspaper brings accounts of the laws violated-not by individuals merely but by organized societies who act in defiance of the lawfully constituted authorities. What a weakness this proves in the government. It appears to me that the moral principle of the nation is much lower than formerly–much less than vanity will allow. Americans are too fond of attributing the great prosperity of the country to their own good government instead of seeing the source of it in the unbounded resources and favorable political opportunities of the nation. It is with sorrow that I anticipate the downfall of pure republican government. Its destruction will be a death blow to Freedom, for if the free government of the United States cannot exist a century where shall we turn? The hope of the wise and the good will have perished, and scenes of tyranny and wrong, blood and oppression, such as have been acted since the world was created, will be again performed as long as man exists. There is no perfectibility in this world. Evil seems necessary for the production of good and good is like a stream flowing swiftly towards a precipice and dashes down. The tumultuous waters below are the same as those above, but those above in the smooth stream are pure, those below are turbid. May my fears be foolish, a few years will tell.

Cole cherished the potential that the new American nation represented. But with any true and deep love comes fear of the worst, the potential for a great and wonderful thing to be manipulated into its inverse. During Cole’s time, the possibility of civil war and the fight for the spirit of the new American nation was brewing. The cultural foundation of the country was the seed that needed not only planting, but cultivation if it were to bear future fruit. This is why Cole implored his fellow Americans to understand art and the power it possesses — to harness it for the Good, for the sake of the future of the nation and to learn the mistakes of the Old World. In his 1845 Lecture on Art, Cole wrote:

But not by the mere imitation of what has been before done, nor the subservient copying of Art in her Ancient forms can a great Era of Art be attained by us, but by working under the great principles which governed Greek and Italian Art, and as new requirements, new moral and religious aspects in Society present themselves, apply those principles. … Let us endeavor then to lift up the prostrate standard of Art and make a stand against this headlong Utilitarianism which prevails. Let us try to convince our fellow Citizens that the pursuit of the beautiful is as essential to our well being as that of Gain. Gold can purchase food, raiment, property, but Taste is that Gentle and refined Spirit which bestows on life its serenest pleasures and most exquisite delights. Without Art Man would scarce be human; with it he rises above the brute and takes a diviner nature.

To prevent the self-destructive course of empire, man needs Art. And I’m not speaking of Art in terms of how it’s understood today. The sad state of what is considered Art in the modern age is almost always purely libidinal, hedonistic, or just plain nihilistic; infantile ‘art for art’s sake’ or every human emotion as a ‘valid’ expression that deserves attention. But rather, Cole’s emphasis was on the epistemology of Art itself. Cole was a critic of the critics, because he saw them as the priesthood which would cultivate taste within the public, or lack thereof. The Art of today’s modern Western world is a naked emperor situation. Those within institutions make fools of themselves by describing how a Rothko painting moved them to tears, while those who are earnest enough to say “I don’t get it” are considered uncultured rubes. The general public is therefore artificially divided into phonies and hillbillies.

Cole’s Hudson River School stood in direct opposition to what the institution of Art now stands for. In 1840, Cole wrote “A Letter to the Critics on the Art of Painting” published in The Knickerbocker: or, New-York Monthly Magazine. In the letter he explains:

… the art of painting is not merely a thing for amusement: it may amuse, as your criticisms may; but it has higher aims, as your critiques may also have. It is, in its higher departments, the imitation of the creative power. It forms, on the principles of eternal nature, a world of its own. Its influence on man, morally and intellectually, has been and is far more extensive than many of you have ever dreamed of. In ages past, it has made moral and religious impressions on the mind and character of nations, that are not yet effaced. It is an engine capable of great good, or great evil. It speaks a language intelligible to all nations, and to all ages. In the Historical productions of the art, the mind is impressed with all the power of reality; in the Imaginative, it is transported above the common sphere of humanity; in the Familiar, it illustrates a moral, or inculcates the affections; in Still-life it may amuse the eye, and hold, for many seasons, the beauty which in nature perishes in an hour. It is capable of imparting knowledge, and awakening the soul to the refining influences of beauty and sublimity. Such being the exalted character of the Art of Painting, we ought to approach it with reverence, and criticize it with that knowledge which is the result of patient study, and with a conscientious desire for the advancement of true taste.

How does a Rothko or Pollock “painting” influence man morally and intellectually? Are these engines of great good or evil? Truly great art is intelligible to all people across, nations and ages — any type of background or subcategory you could name. Great art elevates mankind — which he first sees as beauty, but later recognizes as truth.

What now as beauty thou dost know,

-Schiller

shall one day come to thee again as truth.

This truth is beyond the realm of material reality. This is the reason that Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School art movement was founded on the idea that Art is what separates mankind from animal.

Without Art Man, would scarce be human; with it he rises above the brute and takes a diviner nature.

Real art can pierce through time with its depiction of events through the eyes of universal history, offering mankind a vantage point beyond the scope of its current existence. This quality of thinking increases our ability to make good decisions and take part in consciously moving the universe towards ever increasing perfectibility, and is required if a society hopes to chart a course out of the imperial shackles which have driven it to the edge of its own self-induced annihilation. As Cole said,

Art is in fact man’s lowly imitation of the creative power of the Almighty.

Cole’s Course of Empire was a direct warning to the American people, both in his time and the future. In other words, us. A tremendous effort has been, and is still being made by the Empire to jam that signal. Luckily for us, real beauty can not be destroyed, and truth is eternal. It’s up to us to choose to see it.

This article was originally published in Leonore Magazine – Art, Science and Statecraft

Leave a Reply